A post drifted into my social feed recently that made me smile: “My ability to remember lyrics from the 80s far exceeds my ability to remember why I walked into the kitchen.”

It’s humorous because it’s true; I call these ‘brain farts’ and they happen often for me! This witticism highlights how memory operates, and perhaps more interestingly, it got me thinking about how our companion animals experience the world.

Do you have to let it linger?

Back in 1993, the Cranberries album Everybody Else Is Doing It, So Why Can’t We? was released which included their smash hit ‘Linger’. When this song hit the UK Top 10, I was amidst a teenage breakup; my 18-year-old self was devastated. The tune soon became an auditory anchor, and an overwhelming sadness would occur (and still today) in the pit of my stomach each time it played on the radio (an auditory anchor is a sound, word, or phrase associated with a specific state, emotion, or behaviour).

If you’re like me and can recall every lyric from an old tune, like The Cranberries’ Linger, yet routinely forget why you opened a cupboard, it is OK! It’s your memory prioritising! That’s because human memory operates within a complex interplay of systems that categorise, filter, and encode information based on its perceived importance.

Memories anchored in music, particularly from emotionally resonant periods like adolescence, are reinforced through repetition and affect. Songs with rhythm, narrative, and nostalgia are processed by the hippocampus, consolidated into the neocortex, and steeped in emotional resonance by the prefrontal cortex (Levine et al., 2004). That’s why Linger survives in my brain, while my intention to go into the kitchen to get my dog’s lead disappears into the ether!

Additionally, working memory (which holds transient information such as short-term goals) is pretty fragile. Unless actively rehearsed, it typically retains data for less than thirty seconds (Cowan, 2008) so, when you find yourself standing in the kitchen with no idea why, your brain is executing its programming, prioritising the emotionally salient, and quietly discarding the rest.

The ‘Doorway Effect’

This then brings me to a cognitive glitch known as the doorway effect. Radvansky et al. (2011) found that walking through a doorway (like the kitchen) can trigger a mental context shift, effectively “clearing the slate” of the brain’s immediate goals. The brain organises experiences as discrete episodes, and a change in physical environment signals the beginning of a new one. This episodic segmentation is efficient from an evolutionary standpoint. That’s because it allows us to focus attention on new surroundings and potential threats or opportunities. However, it also means that the simple act of crossing a threshold can disrupt working memory retrieval.

However, to what extent we “forget” after walking through a doorway may depend on how attentively we held that intention in mind, rather than being a universal cognitive reset. This distinction matters as it highlights that memory lapses are influenced not only by the environment but also by attention, focus, and the presence of competing demands (see cognitive load further on).

By now, you might be thinking, “Hanne, how is this related to animals?“

Well, this phenomenon is not limited to humans. Our companion animals learn in ways that are also highly context-dependent. An example I often use for Puppy & Dog School clients is that they may have taught their dog to sit politely before meals. The behaviour is fluent at home. Yet in a novel setting like a dog-friendly pub, their pooch may be unable to settle, may leap up at the table or towards others. There are likely several factors at play, and a considerable one is a lack of generalisation. Behaviours are not automatically transferred across contexts. Instead, they must be practiced, patiently, in varied environments. So your dog is not being ‘stubborn’ nor has ‘selective hearing’, instead it is a feature of learning known as stimulus control (Bouton, 2004). The dog has learned to associate the cue (e.g. sit) with a specific set of environmental and sensory cues present indoors, and generalisation takes deliberate effort and repetition across multiple contexts. See my article on generalisation for more!

Hence, training success depends on recognising that animals never automatically transfer skills between locations. That is why it is essential to practice cues in different places, under varying conditions, working at your pet’s pace, and this strengthens the likelihood of reliable behaviour, regardless of the setting.

Animals and emotional memory

As highlighted earlier with my Linger teenage heartbreak example, memory is shaped by emotion. In humans and animals, experiences that provoke strong positive or negative feelings are more likely to be remembered. These affective memories are about how it felt. For instance, a cat may not remember every step of a grooming session, but the cat will retain an impression of whether that grooming experience was calm and safe, or distressing and overwhelming. This emotional residue influences future responses to similar situations. This is why it can be so problematic for some owners when it comes to nail trims, vet visits, administering ear drops and so on.

It follows that your tone of voice, body language, and predictability matter greatly. Your animal may not remember the specific cue you gave yesterday, yet they will remember whether those interactions with you are generally rewarding or stressful. This emotional framing forms the backdrop to all learning. This is why your tone, body language, daily interactions with your pets and the emotional environment you create are as important as the training cue itself. This is why when you embark on any animal behaviour change programme or are seeking support from a trainer, you need to know the red flags to watch out for!

This leads me to stress and when it gets in the way.

Human memory is susceptible to cognitive load. When juggling tasks or feeling mentally fatigued, our capacity to hold information in our working memory deteriorates. Stress, in particular, impairs the prefrontal cortex’s function, the area responsible for decision-making, attention, and short-term memory (Arnsten, 2009).

Animals are no different. When they experience elevated stress levels, whether that’s from loud noises, unpredictable environments, inconsistent and or punishment-based handling, this can inhibit learning by impairing memory formation and recall. Again, this is especially relevant in training or behaviour modification work. If an animal is too anxious to focus, they cannot take in new information effectively!

Understanding these memory systems can transform how we approach training, husbandry, and everyday interactions with our animals.

Below are some quick tips to help you and your pets:

- Vary the training environment. Practice your pet’s known cues (e.g., “down,” “come,” etc.) in different rooms, at different times of day, and eventually in outdoor settings in low-level distracting environments. Then, weave in further distractions slowly to build generalisation.

- Keep sessions short and positive. Overloading the animal, especially in novel or stimulating environments, reduces retention. Read my article about maximising motivation to understand more.

- Pay attention to your emotional tone. Speak calmly, offer consistent feedback, and avoid abrupt changes in energy. Your animal’s affective memory is always recording. Click here to learn more about how you talk matters.

- Give yourself and your pet grace. Memory lapses are simply part of how the human brain operates. The same courtesy should be extended to your animal. Give your pet time to process; avoid repeating cues rapidly, like a machine gun firing out bullets, as this can overwhelm or confuse. Research highlights that the dog audio-motor tuning differs from humans’. So, we must adjust our speech rate to improve communication efficacy (Déaux et al., 2024). Additionally, dogs can recognise meaningful phrases (Root-Gutteridge et al., 2025). This means clarity, pacing and content matter. Use consistent wording and give your pet time to process and respond. If your pet gets it wrong, consider what you can do differently to help them understand and succeed next time.

The next time you catch yourself humming an old tune, wondering what you wanted from the kitchen, know that it’s just your brain doing its job. And when your dog seems to “forget” something you thought they knew, consider the context, the emotional environment, and the cognitive demands involved. Memory, it turns out, is less about what’s forgotten and more about what was never quite encoded. Speaking of which, where did I put that lead?

References

- Arnsten, A. (2009) Stress signalling pathways that impair prefrontal cortex structure and function. Nature Reviews Neuroscience. 10, pp.410-422. Available at: doi.org/10.1038/nrn2648

- Bouton, M.E. (2004) Context and behavioral processes in extinction. Learning & Memory. 11(5), pp.485-494. Available at: doi: 10.1101/lm.78804

- Cowan, N. (2008) What are the differences between long-term, short-term, and working memory? Progress in Brain Research. 169, pp.323-338. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1016/S0079-6123(07)00020-9

- Déaux, E.C., Piette, T., Gaunet, F., Legou, T., Arnal, L., Giraud, A.L. (2024) Dog-human vocal interactions match dogs’ sensory-motor tuning. PLoS Biology. 22(11): e3002923. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pbio.3002923

- Levine, B., Svoboda, E., Hay, J.F., Winocur, G. and Moscovitch, M. (2002) Aging and autobiographical memory: Dissociating episodic from semantic retrieval. Psychology and Aging. 17(4), pp.677-689. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1037/0882-7974.17.4.677

- Radvansky, G.A., Krawietz, S.A. and Tamplin, A.K. (2011) Walking through doorways causes forgetting: Further explorations. The Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology. 64(8), pp.1632-1645. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1080/17470218.2011.571267

- Root-Gutteridge, H., Korzeniowska, A., Ratcliffe, V., Reby, D. (2025) Domestic dogs (Canis familiaris) recognise meaningful content in monotonous streams of read speech. Animal Cognition. 28 (29). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10071-025-01948-z

Learn more about our classes

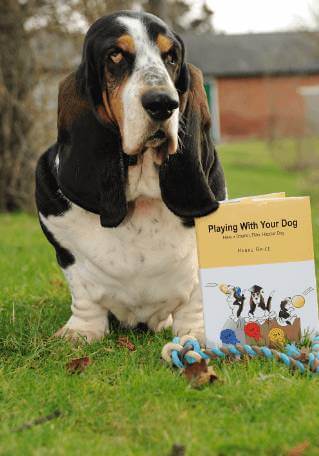

Get Hanne's book, clothing and more

Hanne has a number of publications including her book Playing With Your Dog to help owners work out the games that are best suited for their pet to play throughout his life, from puppyhood to old age, available from Amazon. Check out Hanne's range of contemporary casuals The Collection – for pet lovers made from recyclable, organic materials that are sustainably sourced.